Restoration And Finishing Facts

All Conservators Are Not The Same, Bob Flexner

About 20 years ago at the turn of the 20th century, I was editing Professional Refinishing, a trade magazine that was mailed free to refinishing shops around the country. (Unfortunately, the magazine was dissolved in 2003 because there weren’t enough possibilities for advertising to support it; by far, the primary cost in these shops is labor, not supplies.) One of the trends I noticed among the readership was a tendency to inflate what they called themselves from “refinisher” to “restorer” and from “restorer” to “conservator.” Conservator seemed to occupy the position at the top of the pack. So, what exactly is a conservator? Before explaining this term, I want to point out that there are actually two large categories of conservator: one type is employed by museums; the other works in private practice for clients. It has its own sub-organization within the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC). This sub-group is called Conservators in Private Practice. Though there is some crossover, of course, conservators in private practice work for clients – that is, they aren’t employed directly by museums (or they are employed by museums and work for clients on the side). So a conservator in private practice differs from a restorer primarily by the standards he or she keeps, or at least tries to keep. This is not always easy because in the end both conservators and restorers try to please their clients by giving them what they want.

Background

The field of museum conservation has changed in the last century or two. This has occurred partly because of the improved conditions in museums, primarily temperature and humidity control, and partly because conservators have created standards to be followed with the goal of preserving the history of the furniture, paintings, textiles, or whatever. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the curator (often called a “keeper”) was in total charge of researching, acquiring and exhibiting the objects in the museum’s collection. Sometimes, the curator felt accomplished enough to correct any damage to the objects. Other times, the objects were sent to someone who had the skills. Decisions for what to do were made by how easy the repairs were and by the appearance. “If it looks good, it is good” was the standard. The problem was that this approach led to the removal of much of the history of the object. And as time went on, preserving the history rose in importance. This led to the establishment of AIC in 1972 with only a few members to begin with, but now totaling over 3500 worldwide. It also led to the eventual creation of a code of ethics. You can read this code at www.culturalheritage.com.

Conservation

What this code did was make conservation professionals much more scientific in determining what should be done. They started paying attention to the chemical interaction between the original materials and the restoration materials being used. The techniques of microscopic examination and chemical analysis could be used on a cross-section of finish layers to determine what the original finish was. With this information, they could decide whether or not to try removing the added layers to get back to the original finish. This is commonly done by painting conservators, but there is a caveat. The original painting materials were usually oil paints, and later materials were most often shellac or some similar alcohol-soluble coating. This could be removed with alcohol without disturbing the original. But the order in furniture was most commonly the opposite. The original was an alcohol soluble resin, and the added might be a varnish or even a catalyzed finish if done more recently. It’s much more difficult to remove these coatings without also removing the original. As you would expect with the increased emphasis on chemical analysis, there are now several universities in the U.S. and other countries that offer degrees in conservation. They usually begin with a knowledge of organic chemistry. The goal is to preserve as much of the history of the object as possible, along with long-term stability.

Restoration

There has always been a tension between the object as history and the object as functional. When the object will be preserved in a museum, the history can take priority. But when it is in the possession of individuals, the functional part usually takes priority. The owner usually wants to use the object and to love it for its beauty. Some years ago, on several trips to New York and New England, I made an effort to visit many of the leading antique dealers. The one thing I found most striking was that almost all of the furniture had been fairly recently refinished. The old finish had been removed and a new one applied. As a refinisher myself, I recognized this immediately. This was soon after the Antiques Roadshow had become a popular TV show on public television. The message of this show when it comes to furniture was clearly, “Don’t refinish. You’ll destroy the value.” So I asked the owners of these galleries if this show wasn’t causing them problems with sales. Quite to the contrary, each dealer explained, people in the market for this quality of antique furniture knew better. They wanted beautiful, functional objects, and keeping the “crusty craze” of original finishes didn’t sell. So these dealers were simply responding to the marketplace. Where the tension between preserving the history vs. making the object functional becomes evident is with conservators in private practice, working for individual people or businesses rather than museums. In my experience (and I have known many of these conservators), they often, or maybe I should say “usually,” break with the code, because keeping to it wouldn’t give their clients what they want. For the longest time I struggled with this because I thought of all conservators as the same, and I knew so many who didn’t follow the code very tightly. It wasn’t until I realized that conservators working for individuals rather than in museums needed to be thought of differently. In many cases, they are more like restorers than conservators working in museums.

Bob Flexner is the author of “Understanding Wood Finishing,” and “wood finishing 101

All Conservators Are Not The Same, By Bob Flexner

About 20 years ago at the turn of the 20th century, I was editing Professional Refinishing, a trade magazine that was mailed free to refinishing shops around the country. (Unfortunately, the magazine was dissolved in 2003 because there weren’t enough possibilities for advertising to support it; by far, the primary cost in these shops is labor, not supplies.) One of the trends I noticed among the readership was a tendency to inflate what they called themselves from “refinisher” to “restorer” and from “restorer” to “conservator.” Conservator seemed to occupy the position at the top of the pack. So, what exactly is a conservator? Before explaining this term, I want to point out that there are actually two large categories of conservator: one type is employed by museums; the other works in private practice for clients. It has its own sub-organization within the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC). This sub-group is called Conservators in Private Practice. Though there is some crossover, of course, conservators in private practice work for clients – that is, they aren’t employed directly by museums (or they are employed by museums and work for clients on the side). So a conservator in private practice differs from a restorer primarily by the standards he or she keeps, or at least tries to keep. This is not always easy because in the end both conservators and restorers try to please their clients by giving them what they want.

Photo on left (The stripping process, the stripper has ben applied and I am now removing finish by scubbing with steal wool)

Background

The field of museum conservation has changed in the last century or two. This has occurred partly because of the improved conditions in museums, primarily temperature and humidity control, and partly because conservators have created standards to be followed with the goal of preserving the history of the furniture, paintings, textiles, or whatever. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the curator (often called a “keeper”) was in total charge of researching, acquiring and exhibiting the objects in the museum’s collection. Sometimes, the curator felt accomplished enough to correct any damage to the objects. Other times, the objects were sent to someone who had the skills. Decisions for what to do were made by how easy the repairs were and by the appearance. “If it looks good, it is good” was the standard. The problem was that this approach led to the removal of much of the history of the object. And as time went on, preserving the history rose in importance. This led to the establishment of AIC in 1972 with only a few members to begin with, but now totaling over 3500 worldwide. It also led to the eventual creation of a code of ethics. You can read this code at www.culturalheritage.com.

Photo on right (This19th Century Provincial oak-carved armoire had to be re-glued and the crown had to be re-glued and refitted. I also restored the finish.)

Conservation

What this code did was make conservation professionals much more scientific in determining what should be done. They started paying attention to the chemical interaction between the original materials and the restoration materials being used. The techniques of microscopic examination and chemical analysis could be used on a cross-section of finish layers to determine what the original finish was. With this information, they could decide whether or not to try removing the added layers to get back to the original finish. This is commonly done by painting conservators, but there is a caveat. The original painting materials were usually oil paints, and later materials were most often shellac or some similar alcohol-soluble coating. This could be removed with alcohol without disturbing the original. But the order in furniture was most commonly the opposite. The original was an alcohol soluble resin, and the added might be a varnish or even a catalyzed finish if done more recently. It’s much more difficult to remove these coatings without also removing the original. As you would expect with the increased emphasis on chemical analysis, there are now several universities in the U.S. and other countries that offer degrees in conservation. They usually begin with a knowledge of organic chemistry. The goal is to preserve as much of the history of the object as possible, along with long-term stability.

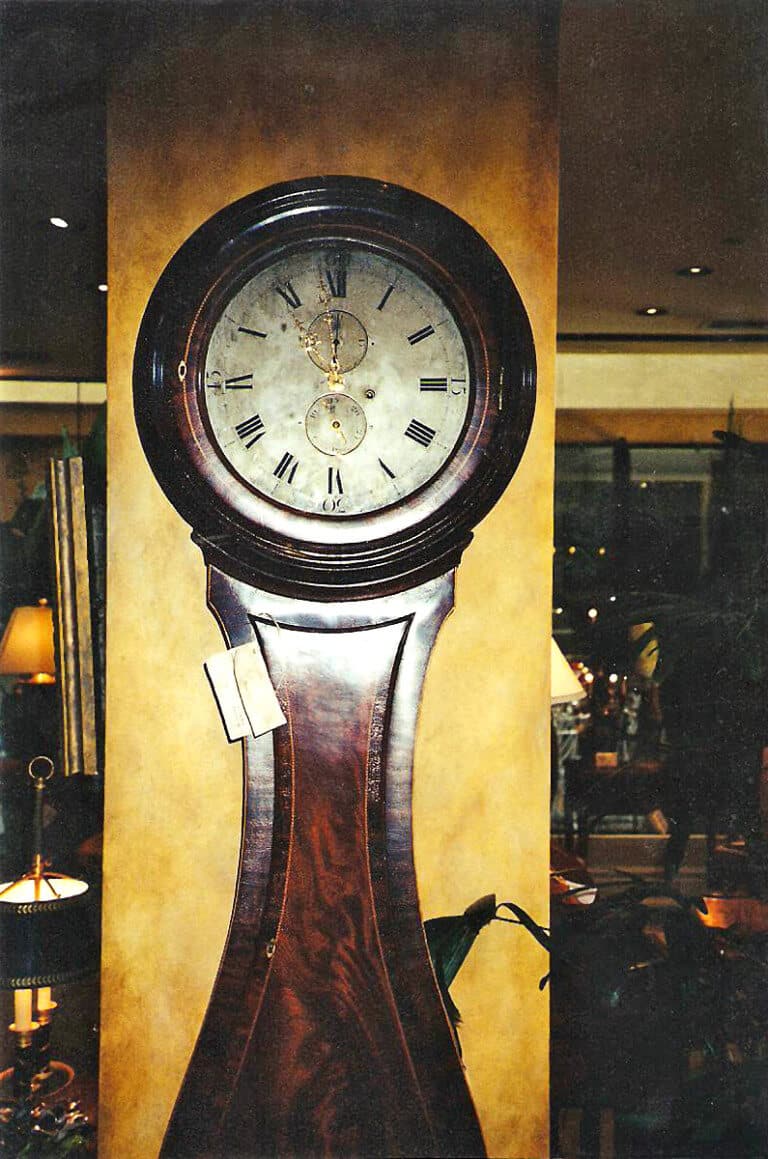

Photo on left (Repaired and restored 1800’s clock.)

Restoration

There has always been a tension between the object as history and the object as functional. When the object will be preserved in a museum, the history can take priority. But when it is in the possession of individuals, the functional part usually takes priority. The owner usually wants to use the object and to love it for its beauty. Some years ago, on several trips to New York and New England, I made an effort to visit many of the leading antique dealers. The one thing I found most striking was that almost all of the furniture had been fairly recently refinished. The old finish had been removed and a new one applied. As a refinisher myself, I recognized this immediately. This was soon after the Antiques Roadshow had become a popular TV show on public television. The message of this show when it comes to furniture was clearly, “Don’t refinish. You’ll destroy the value.” So I asked the owners of these galleries if this show wasn’t causing them problems with sales. Quite to the contrary, each dealer explained, people in the market for this quality of antique furniture knew better. They wanted beautiful, functional objects, and keeping the “crusty craze” of original finishes didn’t sell. So these dealers were simply responding to the marketplace. Where the tension between preserving the history vs. making the object functional becomes evident is with conservators in private practice, working for individual people or businesses rather than museums. In my experience (and I have known many of these conservators), they often, or maybe I should say “usually,” break with the code, because keeping to it wouldn’t give their clients what they want. For the longest time I struggled with this because I thought of all conservators as the same, and I knew so many who didn’t follow the code very tightly. It wasn’t until I realized that conservators working for individuals rather than in museums needed to be thought of differently. In many cases, they are more like restorers than conservators working in museums.

Bob Flexner is the author of “Understanding Wood Finishing,” and “wood finishing 101